The conviction that a situation – previously understood as given – can be altered, provides the starting point for people to come together, define a common agenda, and attempt to acquire power. But how does this process from articulation to mobilization take shape in different historical settings? From 24 to 27 June 2025, the Summer School of the Onderzoeksschool Politieke Geschiedenis, hosted at the University of Amsterdam, explored this question. Looking for politics on the streets, interviewing people, and visiting local research institutions, we developed our insights in constant dialogue with the city around us.

The conviction that a situation – previously understood as given – can be altered, provides the starting point for people to come together, define a common agenda, and attempt to acquire power. But how does this process from articulation to mobilization take shape in different historical settings? From 24 to 27 June 2025, the Summer School of the Onderzoeksschool Politieke Geschiedenis, hosted at the University of Amsterdam, explored this question. Looking for politics on the streets, interviewing people, and visiting local research institutions, we developed our insights in constant dialogue with the city around us.

To structure our analyses of trajectories of political mobilization, the participants examined the role of ideas, institutional settings, and practices on three consecutive days. On Tuesday morning, participants examined the role of ideas in political mobilization, focusing specifically on the circumstances under which ideas may gain traction. This theoretical discussion was followed by a city walk in the afternoon, in which participants collected examples of political articulation – ranging from a squatter’s house to stickers, and from a fence to statues – on the streets, which were discussed in a closing session at the end of the day.

The different places where people practice politics shape their repertoire, opportunities for collaboration, and chances for achieving impact. On the second day of the summer school, we explored scholarship on these different institutional contexts, ranging from the way social movements have taken shape to the way politics have taken shape in parliaments and governments, as well as the way circles of experts have attempted to impact political agendas. Instead of understanding political mobilization from a bottom-up and top-down perspective, we explored the ways in which people try to shape politics from different vantage points and how their attempts interrelate. In the afternoon, we pursued practical insights on these questions by interviewing people involved in municipal and environmental politics, diaconal initiatives, journalism, photography, asking how they understood their own position and how they attempt to influence political agendas through their work.

On day three, we analyzed the role of practices within articulation and mobilization. We discussed to what extent collective repertoires of action are a prerequisite of (successful) attempts to impact the political system, or whether individual practices or forms of ‘everyday resistance’ should also be taken into consideration. The group also discussed the difference between modern and early-modern political practices and concluded that the nineteenth and twentieth century forms of collective repertoires differ from those in earlier (European) settings, but that older types of political practices, especially in urban settings, continue to this day. The discussion on differences between older and more recent types of political practices led to a fruitful debate on how to define ‘the political’, and how the process from articulation to mobilization has played out in different historical contexts.

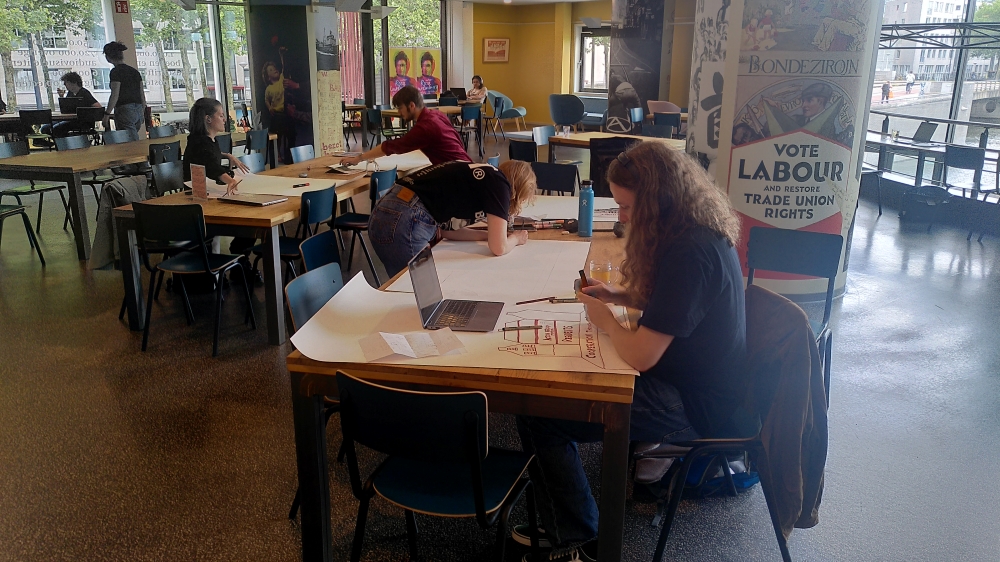

The day continued with the practice of writing (political) history. Over lunch, professor of Urban History Maartje van Gelder discussed the politics of archives. Taking her cue from Venetian archives, she pointed out how archival collections privilege not just certain groups of people but also ideas about the state they live in. Subsequently, we visited the research institutions NIOD, IHLIA, and the IISH in three separate groups. There, we had the opportunity to consider the political dimensions of collecting, storing, and presenting archival material. The participants also worked on a poster presentation. In doing so, they asked how the insights from the readings, discussions, excursions, and interviews applied to their own research on topics as diverse as local environmental activism, conspiracy theories, political ideologies in Germany, and sexual norms.

During our final day of discussions, we concluded that, if we regard the political as a dimension of all relations rather than a phenomenon limited to a distinct sphere or institution, this shifts the questions we ask as political historians. How do politics take shape in different ways according to the place, time, and actors involved? For this analysis, we found it helpful to look at distinct phases in the process of mobilization – everyday resistance, articulation, mobilization, institutional trajectories. Instead of employing a distinction between public and private, we focused on the distinct dynamics of the places in which politics take shape. The summer school thus offered an opportunity to explore specific questions as well as overarching perspectives on political mobilization.